Germany’s debt brake reform: A push for intergenerational fairness

Germany is facing increasing pressure to reform its strict debt brake rules, with policymakers advocating for changes that balance fiscal responsibility and long-term investment. The current framework, which significantly limits government borrowing, has been criticized for hindering public investment and placing an unfair burden on future generations. Experts argue that a revised intergenerational debt rule is necessary to ensure economic stability, infrastructure development, and sustainability while preventing excessive debt accumulation.

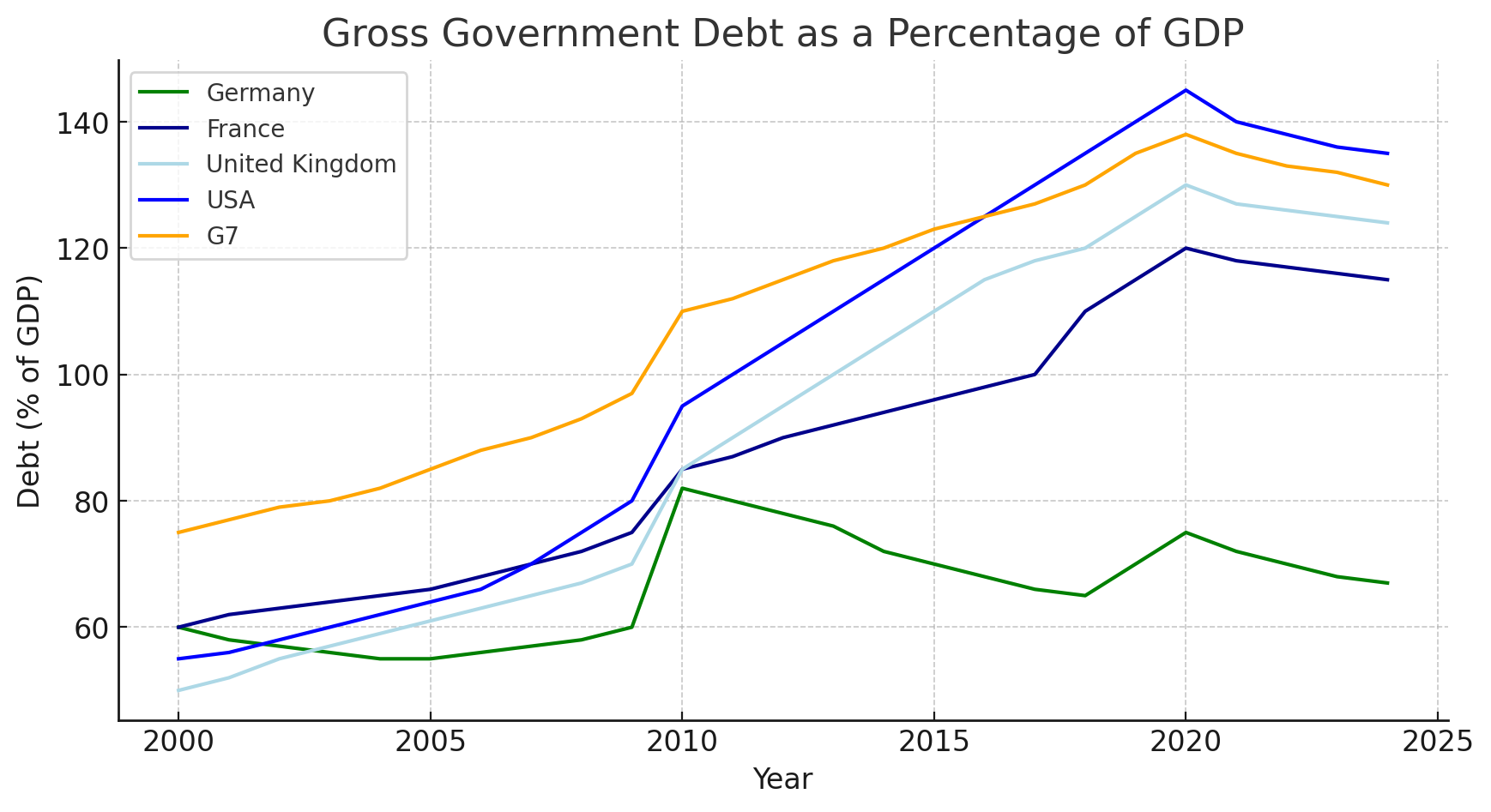

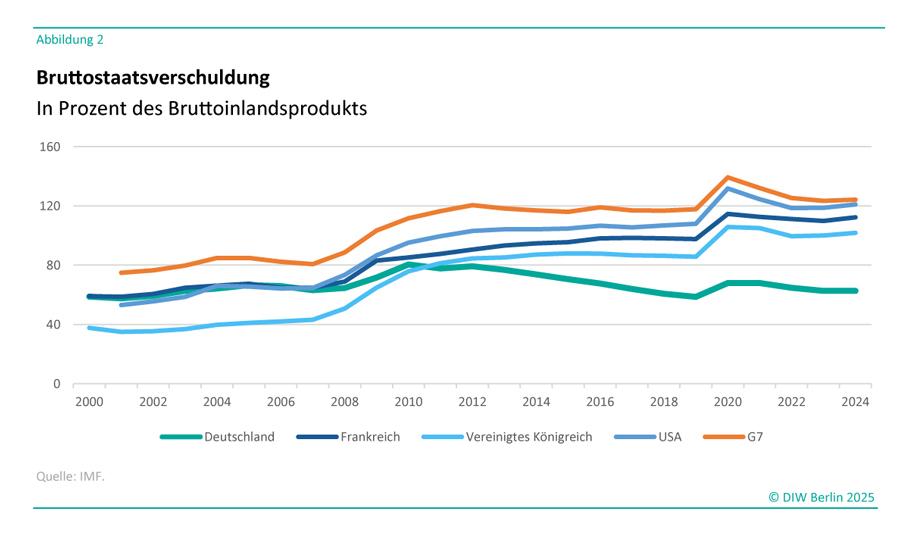

The debt brake, introduced into Germany’s Basic Law in 2009, restricts the federal government’s structural new debt to 0.35% of GDP annually, allowing for minor flexibility in economic downturns. The Federal Constitutional Court further tightened its application in a landmark ruling in November 2023, making it harder for governments to justify exceptions. Supporters of the rule argue that keeping debt levels low ensures economic resilience and prevents future financial crises. However, critics contend that it prevents essential investments in infrastructure, digitalization, education, and climate protection, ultimately harming future generations rather than securing their prosperity.

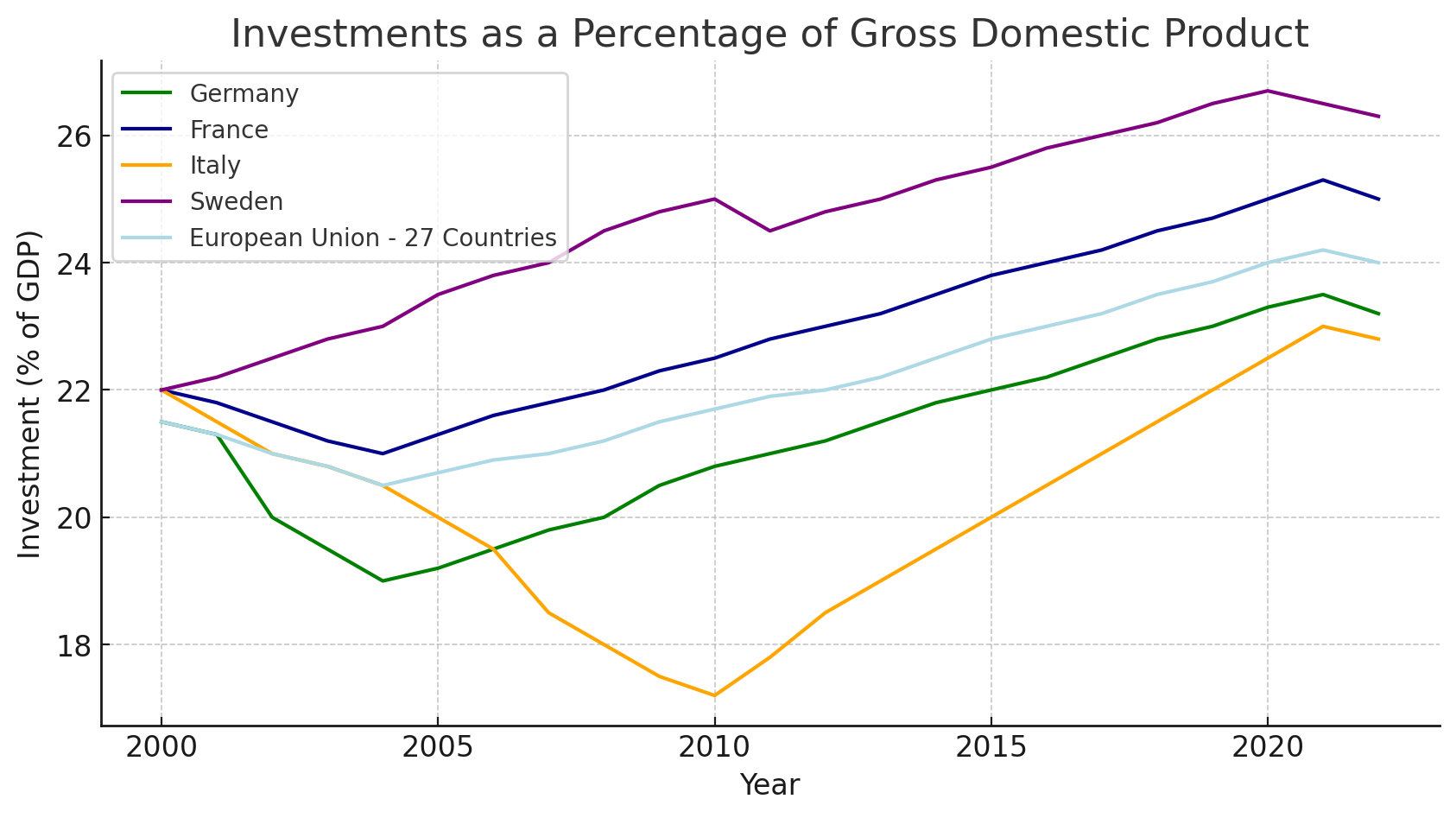

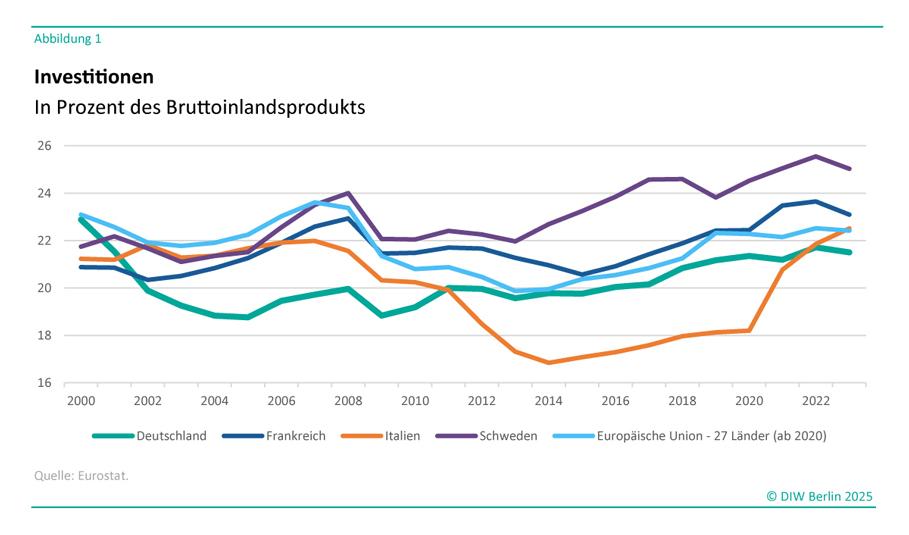

A proposed reform introduces four key changes aimed at balancing fiscal discipline with economic growth. The first change suggests a nominal expenditure rule, allowing debt to grow in line with nominal potential GDP growth rather than being arbitrarily capped. This adjustment would stabilize Germany’s debt ratio at around 60% of GDP, aligning it with European fiscal norms while ensuring the state can act during economic downturns. The second change calls for reintroducing a Golden Rule, which would exempt public investment from debt limits, ensuring net investment remains positive to prevent deterioration of public infrastructure. Meanwhile, public consumption spending would shrink proportionally to demographic changes, optimizing government expenditure efficiency.

The third aspect of the reform focuses on implicit sovereign debt, including long-term liabilities in social security and climate adaptation costs. Currently, Germany’s aging population and increasing climate-related obligations pose significant financial risks. Under the proposed rules, these liabilities should decrease in line with declining employment potential to prevent overburdening younger generations. The final pillar of the reform addresses equity in government spending, ensuring that investments benefit all social groups, particularly those in structurally weaker regions. This measure aims to secure equal opportunities and a fairer distribution of public resources.

The debate over reforming the debt brake has gained momentum as even traditionally conservative parties, including the CDU/CSU, acknowledge the need for adjustments. With Germany’s economic future at stake, policymakers face a crucial decision: maintain a rigid fiscal policy that limits growth or adopt a modernized debt rule that balances sustainability with economic progress. Whether this reform moves forward depends on political consensus, but one thing is clear: Germany must rethink its approach to public debt if it wants to ensure prosperity for future generations.

Source: DIW Berlin