OECD Warns: Rising debt levels pose risks to future investment capacity

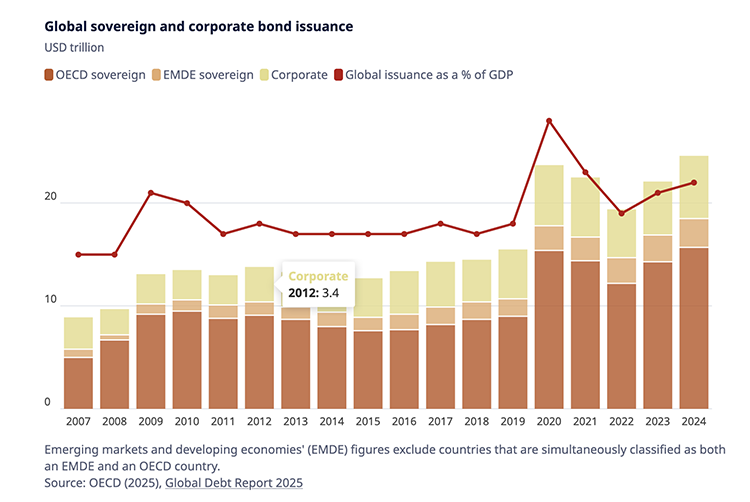

Governments and corporations significantly increased their borrowing in 2024, raising a total of USD 25 trillion from financial markets. This figure is USD 10 trillion higher than levels seen before the COVID-19 pandemic and nearly triple the amount borrowed in 2007, according to the OECD’s Global Debt Report 2025: Financing Growth in a Challenging Debt Market Environment.

The report finds that both sovereign and corporate debt levels are expected to grow further in 2025. The marketable debt-to-GDP ratio for central governments in OECD countries is projected to reach 85%, up by more than 10 percentage points from 2019 and nearly twice the ratio seen in 2007. At the same time, bond yields have increased in key markets, even as policy interest rates have started to decline, making new borrowing more costly.

The rising cost of debt, coupled with already elevated debt levels, risks limiting the ability of governments and companies to finance future investments. Much of the borrowing over the past decade and a half has been used to manage economic shocks, notably the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, additional investment will be needed to address long-term priorities such as economic growth, productivity, demographic shifts, and defence spending.

OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann noted that the current environment demands more efficient public spending and a focus on borrowing that supports long-term productivity. He also stressed the need for policies that encourage businesses to direct borrowing toward investment rather than financial restructuring or shareholder distributions.

Sovereign bond issuance in OECD countries is expected to rise to USD 17 trillion in 2025, up from USD 14 trillion in 2023. Total outstanding sovereign debt is projected to reach nearly USD 59 trillion by 2025, an increase from USD 54 trillion in 2023.

Emerging markets and developing economies have also seen rapid growth in sovereign borrowing, increasing from around USD 1 trillion in 2007 to more than USD 3 trillion in 2024. China alone accounted for 45% of total issuance in 2024, a substantial increase from its 17% share during 2007–2014.

The global stock of corporate bond debt reached USD 35 trillion at the end of 2024, resuming a trend of continuous growth that paused briefly in 2022. The bulk of this increase has come from non-financial companies, whose outstanding debt has nearly doubled since 2008. However, much of this corporate debt has been used for financial operations—such as refinancing or shareholder returns—rather than for investment in new projects or productivity improvements.

Governments are already feeling the pressure of higher borrowing costs. In 2024, interest payments as a share of GDP increased in around two-thirds of OECD countries, reaching an average of 3.3%—exceeding average spending on defence. This rise in interest obligations also raises refinancing concerns, with nearly 45% of sovereign debt in OECD countries set to mature by 2027. Similarly, about one-third of all outstanding corporate bonds will mature within the next three years.

Central banks continued to reduce their presence in sovereign debt markets throughout 2024. Their share of domestic sovereign bonds in OECD countries dropped from 29% in 2021 to 19% in 2024. In contrast, domestic households increased their share from 5% to 11%, while foreign investors’ share rose from 29% to 34%. Sustaining current levels of debt will likely require more involvement from price-sensitive investors, potentially adding volatility to the markets.

This year’s report also includes a thematic analysis of climate finance. It finds that at current growth rates in public and private investment, advanced economies would not meet the Paris Agreement goals until 2041. The outlook for most emerging markets is more challenging, with alignment unlikely before 2050 without significant policy changes.

Meeting global climate targets would require a sharp increase in public spending, adding further to debt burdens. Alternatively, greater reliance on private investment would necessitate rapid capital market development, especially in emerging markets. The OECD stresses that financial regulatory reform will be crucial to unlocking the full potential of debt markets for climate transition financing.