Refugees feel less welcome in Germany, but almost all aspire to citizenship

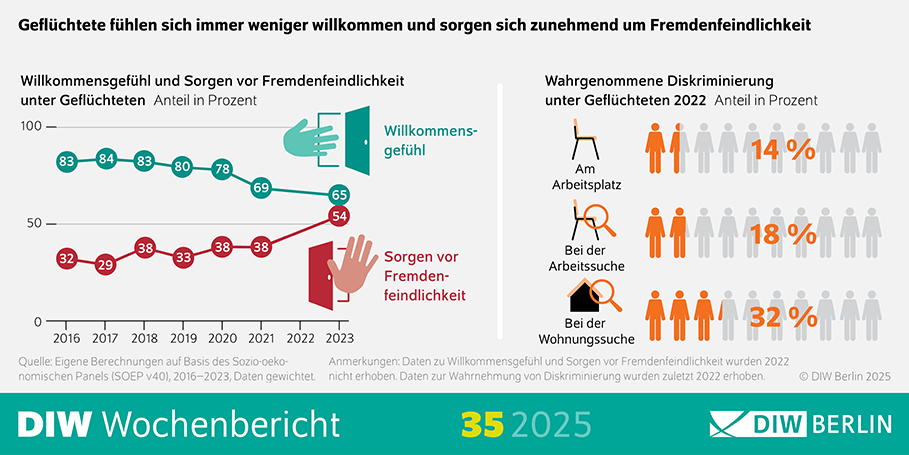

Ten years after Angela Merkel’s famous “We can do it” declaration during the height of refugee arrivals, many refugees in Germany report feeling less welcome than when they first arrived. At the same time, concerns about xenophobia have increased, according to three new studies by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin). The research, based on data from the IAB-BAMF-SOEP survey of refugees who arrived between 2013 and 2019, reveals a complex picture of integration progress and ongoing challenges.

The studies show that perceived discrimination is particularly pronounced in the labour and housing markets. Around 30 percent of refugees say they have experienced discrimination while looking for housing, often due to their ethnic background, religion, or physical appearance. The perception of bias varies: male refugees in eastern Germany report significantly higher levels of discrimination than those in western regions. “Discrimination is not an isolated experience for refugees, especially in the housing market. This not only undermines integration but also risks weakening social cohesion,” said study author Ellen Heidinger, suggesting that transparent allocation systems and anonymous applications could improve fairness.

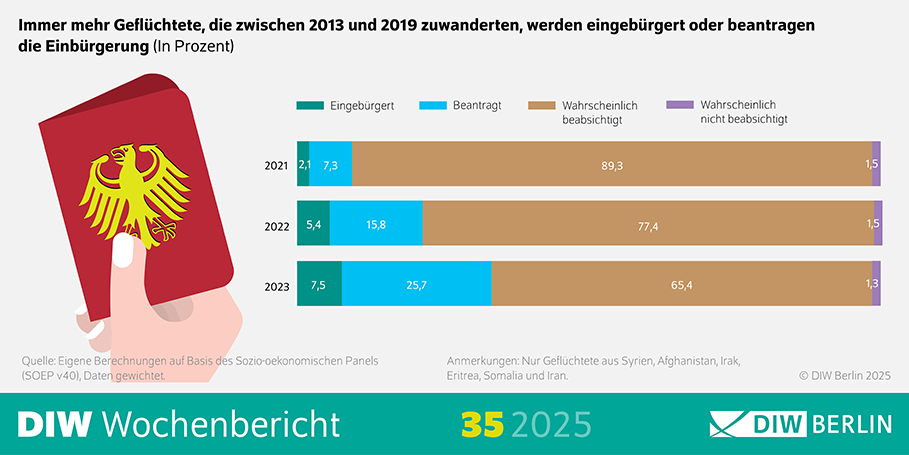

Despite these challenges, the desire for naturalisation remains overwhelmingly high. Between 2013 and 2019, almost all refugees expressed an intention to apply for German citizenship. By 2023, the proportion of naturalised refugees had increased to 7.5 percent, compared with just 2.1 percent in 2021. Applications also surged, with more than a quarter of refugees submitting citizenship requests, and another 65 percent planning to do so. Fewer than two percent said they had no intention of applying. Recent reforms to Germany’s nationality law, which shorten the residence requirement but tighten conditions for financial independence, may slow progress for vulnerable groups such as single parents and low-skilled workers. “Naturalisation is a key step toward full participation, but the reform risks excluding exactly those who need it most,” said study author Jörg Hartmann.

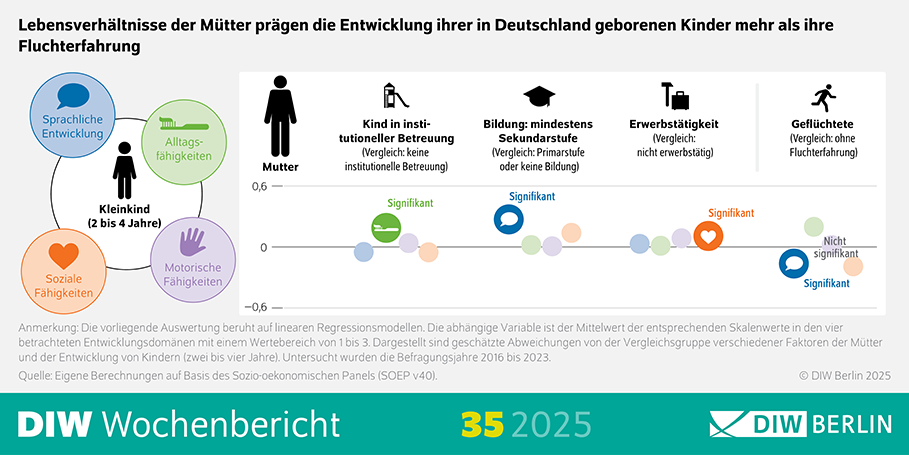

The research also examined the development of children born in Germany to refugee mothers. At birth, no significant differences were found compared with other children in Germany in terms of health indicators such as weight, length, or delivery method. Differences appeared later in early childhood, particularly in language, motor skills, and social development. These disparities, however, were linked not to the mothers’ refugee experiences but to broader social and structural factors including maternal education, mental health, employment, and access to childcare. “It is living conditions, not the fact of flight itself, that shape the development opportunities of children,” said study author Sabine Zinn.

Overall, the assessment ten years on is mixed. Most male refugees have entered the labour market, but female refugees remain significantly underrepresented in employment. Almost all aspire to naturalisation, indicating a strong intention to remain in Germany. Yet barriers persist in the form of limited educational opportunities, uneven labour market integration, and widespread concerns about discrimination and xenophobia. “Integration unfolds at different speeds across different areas,” noted DIW Fellow Cornelia Kristen. “Only with long-term data can we see how naturalisation, employment, and the second generation develop.”

The findings highlight both the progress refugees have made in Germany and the structural hurdles that continue to complicate their path to full participation.

Source: DIW Berlin