2025-09-28

indicators

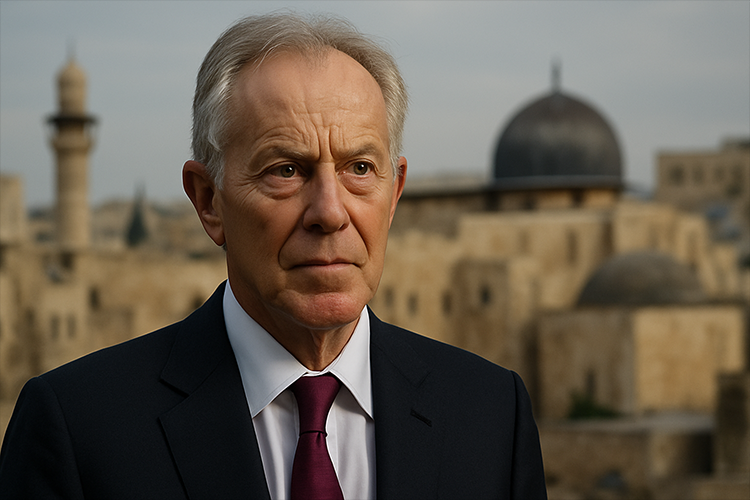

Tony Blair, once Britain’s longest-serving Labour prime minister, has remained an active and controversial figure in global affairs nearly two decades after leaving office. His name has surfaced again in discussions around Gaza, where international actors are exploring the creation of a transitional authority to guide the territory out of the current conflict. While nothing has been confirmed, diplomatic circles have floated Blair as a possible leader of such an interim structure, a prospect that has been greeted with both interest and suspicion. Blair’s involvement in the Middle East is not new. He spent eight years as envoy for the Quartet of the UN, US, EU and Russia, building relationships in the region and carving out a reputation as a broker of complex negotiations. Yet his legacy remains overshadowed by the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which continues to colour perceptions of his judgment and integrity. The Chilcot Inquiry, published years later, criticised the decision-making process that led Britain into war, but it did not find him legally liable. This divide between moral outrage and legal accountability has ensured that the question of Blair’s suitability for any new Middle East role is fiercely debated. Central to the discussion is the question of whether Blair, now at the helm of the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, would stand to benefit personally from such an appointment. The institute, which provides advisory services to governments and works on policy projects worldwide, has grown into a large organisation with hundreds of staff and significant turnover. Recent financial statements show Blair himself receives no salary from the institute, though other directors are well paid. Public filings confirm that one senior executive earned over a million dollars in 2023, underscoring the professionalised and well-funded nature of the organisation. At the same time, the institute attracts government and philanthropic funding, including support from US agencies and international foundations, which are subject to audit and disclosure rules. These figures matter because they frame how any future role in Gaza would likely be structured. If Blair were appointed to lead a transitional authority through his institute or an international body, his compensation would almost certainly be limited to expenses or a fixed salary overseen by donors and subject to scrutiny. That arrangement would be very different from the perception of private enrichment that has dogged his post-premiership career, during which he took on lucrative speaking and advisory contracts for banks and governments. Transparency over who pays, how much, and under what terms will be crucial if Blair takes on a new mandate. The wider question is one of trust. To some, Blair’s experience and network make him a pragmatic choice at a moment when Gaza’s future governance is deeply uncertain. To others, his record in Iraq and his past commercial work disqualify him from a role that would require broad legitimacy among Palestinians and regional stakeholders. In this tension lies the enduring challenge of Blair’s career: a politician who still commands global attention, but whose legacy remains contested, and whose every new step is measured against the most controversial decisions of his time in power.